1421

In the Middle Ages, Holland was regularly plagued by major floods. The coast was protected on the west side by a row of dunes. They were often unable to withstand the northwesterly storm, whether or not in combination with high tide. In the east, on the Zuiderzee side, Holland was incised by wide estuaries, which gave the shallow and turbulent water free space.

The Sint Elisabeth flood of 1421 completely swept away the row of dunes behind the Hondsbos near Petten. A large part of the hinterland in the north of Holland was flooded. The row of dunes was restored, but was also swept away again and again during subsequent storms. To better withstand the intrusion of water, the water board board, the Hoogheemraadschap De Hondsbossche and Duinen tot Petten, decided to strengthen the weak spot in the dunes with wooden sheeting and breakwaters.

The materials for those fortifications, especially trees, reed mats and stones, had to come from Vilvoorde by ship. A long route along Gouda, the Spaarne, the IJ and Amsterdam. The route across the Zuiderzee via the open estuaries to Edam and Petten was very treacherous in strong winds. Many ships never arrived. Cutting off via the Zaan was not possible because the two medieval locks in the dam that have closed the Zaan from the IJ since the 13th century were too small for heavy cargo ships.

1544

In 1544, the Hoogheemraadschap took the initiative to build a new lock in the dam in the Zaan. One of the two old locks, the Westzanersluis, was demolished for this purpose. The new lock was as large as that of Gouda and was named the Groote or Hondsbossche Sluis. This lock made the supply of materials for the flood defense system, 50 kilometers away, considerably more reliable, faster and safer. On November 12, 1547, the lock was put into use.

WHAT ELSE WAS PLAYING IN 1544?

In the sixteenth century the areas that now form the Netherlands were under the rule of the Spanish king Charles V. In 1544, Wilhelm van Nassau inherited a small region in France: Orange and decades later grew into the leader of the revolt against Spanish rule and to the father of the country: William of Orange. In America around 1540, the first Spanish colonialists were driven out by the indigenous population. It wasn't until 60 years later that the Pilgrim Fathers would settle on the east coast and never leave. China experienced a cultural and economic heyday under the Ming dynasty. The stable society, free from war, grew to 160 million inhabitants around the middle of the 16e century

The new and much larger lock had (and still has) a wooden bottom, brick walls and a brick roof to absorb the lateral forces. Alkmaar and Westzaan contributed to the financing of the construction and in return were allowed to pass the lock for free. That was a recipe for centuries of struggle with skippers from other municipalities who also wanted to pay nothing. The first tenant and lock keeper, Jacob Coppes, complained about this shortly after the lock was opened. Skippers who, out of anger, sailed against the roof of the lock with their mast up, worked the doors with anchors and also wanted to pass at night. Jacob wanted to sleep at night and, moreover, the eel had to be let through during the migration season, through the rinkets -water hatches- in the lock gates. Coppes, and the lock keepers after him, had a tough job: a lot of disagreement with the skippers about costs, while as tenants they could barely make ends meet. The management of the fish and water levels was partly taken over in 1611 by the construction of a diving lock, between the Hondsbossche and the old medieval lock. Between 1608 and 1718 there was also an 'Overtoom' on Dam Square, to transfer partially completed big ships from the shipyards on the Zaan to the IJ.

1613

Not only the costs of the locks were a source of disagreement in the lock, for centuries the priority rules have also caused a lot of commotion. In 1613, the water board decided that the ferry from Alkmaar to Amsterdam should be given priority over everyone because the traders had to be able to be on time at the stock exchange. Shortly afterwards, some wealthy industrialists and also ships on their way to the morning markets in Amsterdam were given priority. They had to pay a higher fee for the privilege. Two centuries later, this is still being argued about. In 1799 a group of merchants even argued that the lock acted contrary to the principle of equality of the Batavian Revolution. But to no avail: only steamships eventually also acquired the right of priority for passage.

1722

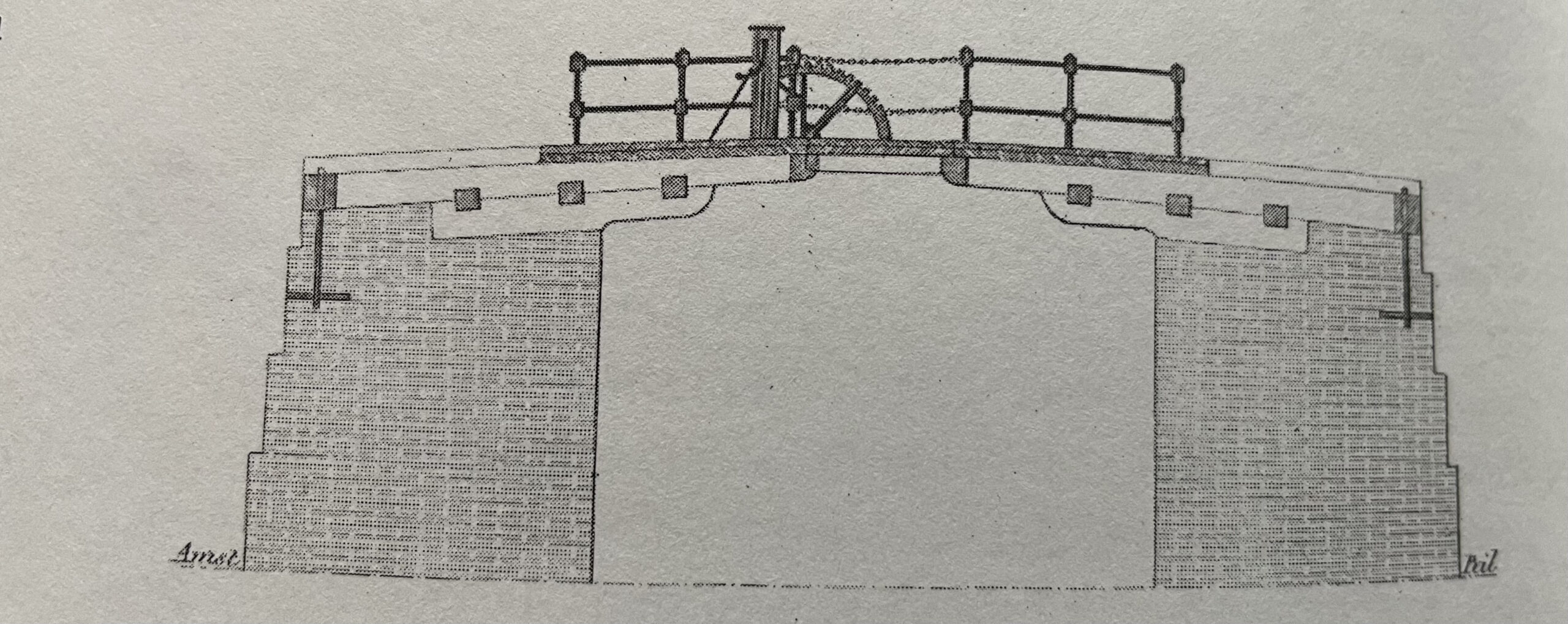

At the end of the seventeenth century, the lock was so damaged and rickety that the leaks made it virtually impossible to pass through. On May 1, 1722, the lock was drained, inspected by the water board board and it was decided to dismantle it. It will be rebuilt in the same place. Just before the completion of the reconstruction, at the end of 1723, the Dijkgraaf decided to build a lockkeeper's house on the east side and a charter house (for collecting excise duties) on the west side. Those houses are still there today, as are the memorial stones that were placed on the south side of the lock at the end of 1724 in memory of the thorough renovation. The renovated lock no longer had a masonry vault but was now closed from above by a fixed bridge. After fifty years of squabbling about financing, a small wooden movable bridge was placed on the vault in 1848, the opening of which could allow the mast of an unsteady vessel to pass through.

In 1865 the movable hatch was replaced by a larger format steel one.

1845

In 1845 the lock was drained again to make repairs. The Hoogheemraadschap van de Uitwaterende Sluizen used that moment to realize a long-cherished wish: installing ebb doors in the lock. In 1641, the Hoogheemraadschap requested this for the first time from the water board of De Hondsbossche en Duinen tot Petten, which still owns the Hondsbossche Sluis. The board was not interested. It felt that the lock had no role in the water management of the Schermerboezem and only wanted to serve the interests of shipping. And that at a time when fresh fresh water in North Holland was becoming increasingly scarce due to reclamations. At low tide, the available fresh water flowed through the automatically opening flood gates of the lock into the IJ. This had major consequences: severe drought on the agricultural land and the wells north of Zaandam. During prolonged drought, salt water was even allowed into the Schermerboezem at high tide, which only increased the damage. For this reason, Uitwaterende Sluizen made regular attempts from 1696 to take over the Hondsbossche lock, but they did not succeed until 1884. That was long after the ebb doors had been installed. By that time, the lock had already lost a lot of importance to shipping due to the construction and commissioning of the Noord-Hollands canal in 1824.

1904

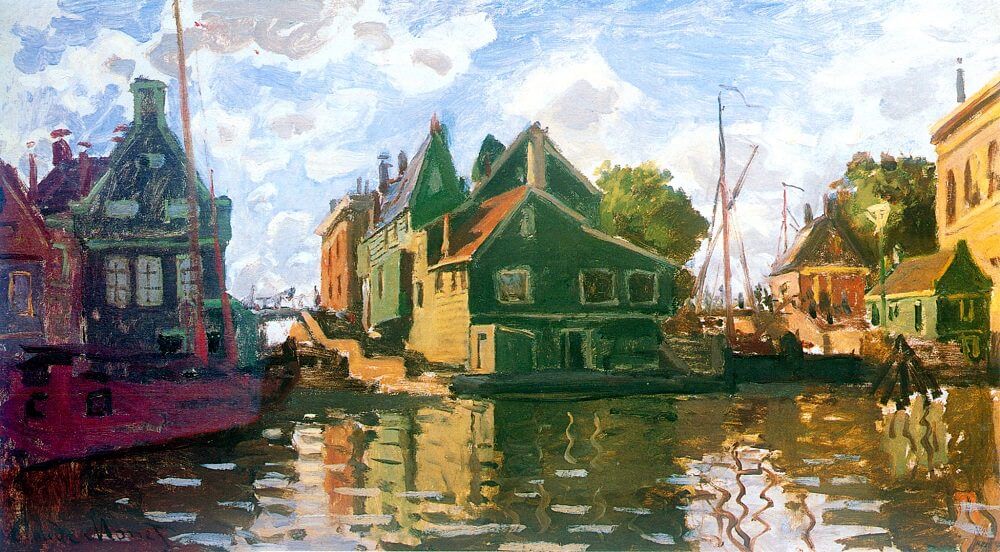

In the nineteenth century, Zaandam developed into a center of often heavy industrial activities. The need for large bulk shipping increased rapidly and the Groote Sluis was increasingly perceived as a bottleneck.

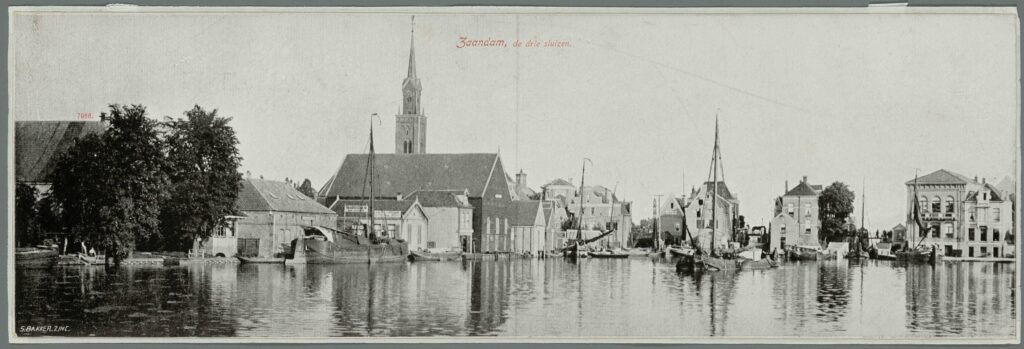

Zaandam wanted to significantly enlarge the lock through a large-scale reconstruction. The water board of Uitwaterende Sluizen, after two centuries of insistence, finally the owner of the lock, however, refused to resell the lock to the municipality. Zaandam therefore decided to build its own, new, much larger lock. The Wilhelmina lock was opened in 1904, right next to the Groote or Hondsbossche lock. The medieval small lock and the diver lock had to be demolished to make room.

The coat of arms of the Hoogheemraadschap Uitwaterende Sluizen, which stood on the diver lock, were first placed on the north side of the new Wilhelmina lock, but were moved to the north side of the Hondsbossche Lock in 1956 when the lock had to be renovated and the Beatrix Bridge was built. They're still there.

1965

The construction of the Wilhelminasluis further reduced the importance of Hondsbossche Sluis for commercial shipping, but it was still an important instrument for water management. That function lost its significance due to the construction of the pumping station between the Wilhelminasluis and the Hondsbossche Sluis in the 1960s. Because of all the construction work on the pumping station and the Beatrix bridge on the soft soil of the island in the Zaan, the lock keeper's house and the excise house, which had subsided seriously, threatened to fall over.

They were carefully demolished stone by stone in 1964 and restored to their original state in 1970. In 1965, the Hondsbossche lock was judged to be superfluous and taken out of use.

2014

In 2013, the order was given to renew and enlarge the Wilhelminasluis. The renovation was originally supposed to take only two years, but the lock did not reopen until 2020. Disagreements with the builder over money and the safety of the lock, a problem that has been recurring at the locks for centuries, have led to many delays. However, this created a new future for the Hondsbossche Sluis: providing access to the Zaan and the North Sea Canal/the IJ for the ever-growing fleet of pleasure craft and small commercial vessels. The lock was festively reopened in 2014.

Zaandam has been the owner of the lock for some time now. With the exception of the new fixed bridge, which has remained at Uitwaterende Sluizen. The Heemraadschap transferred both restored houses in 1997 as cultural heritage to the Hendrick de Keijzer association. Both houses are permanently inhabited.

The lock is operated by volunteers. In 2017, the volunteers were given a new home: the Sloishois. It is a modern design, the most important feature of which is the Corten steel cut-out of a map of the Zaan in 1812, which serves as a roof.